How has this website been built?

If you work in software and you’re wandering around my blog, maybe this is the first question that comes to mind.

Is the blog powered by a CMS? Is it just a static websit, an Angular PWA? Could I build something similar for myself?

If you’ve ever thought about that, you’re in the right place. Let’s start from the beginning.

The origins

When I first bought the domain riccardomaldini.it, turning it into a blog wasn’t part of the plan.

We’re talking about 2018. I was still in university, just starting to dive into the magical world of software development. During a Networking course, I began to understand how the Internet actually worked. This whole network of websites linked together across the world seemed almost magical.

That’s also when I started thinking about my digital identity: what if I bought a domain for myself? The domain riccardomaldini.it was still unused, and it would’ve been a shame if someone else took it and used it for something unrelated to me.

So I decided to buy it. I had no idea what to do with it at the time. I couldn’t even build a website yet, but I wanted to secure it for the future me. On Aruba (the hosting provider I used), the price was ridiculously cheap — something like 3 euros per year — so I didn’t hesitate.

The first real use of the domain came from my Play Store projects. Publishing apps on the Play Store requires providing Google with a webpage containing a Privacy Policy and Terms & Conditions. So I purchased hosting space from Aruba and uploaded a very simple static site with those policies (auto-generated, of course — I’m not a lawyer yet 🙂).

Fun fact: that’s still one of the purposes of the website today (see the BetAssist Privacy Policy, for example).

The first version: a very static CV website

Fast forward to 2021. We’re in the middle of the COVID pandemic. I was in my last year of university with a few exams left, but also with much more experience than before and, for the first time, a lot of free time (thanks, lockdown).

That’s when I started experimenting heavily with web design. I was learning Flutter, Angular, and even some Python/TypeScript for my first web server experiments. I worked on the DiAry project and CovidAnalysis (I’ll definitely talk about those in the future). At the same time, I began experimenting again with my personal website.

My first idea was to turn it into an online CV. I wanted a place to showcase my studies, skills, and (limited) work experience. So I developed the first version: a static, hand-written HTML page with CSS, built on top of a template from html5up.com. Honestly, I think everyone started from there 😄

The first template I used was Photon, a versatile personal template. Then I tried Miniport, which was a bit more CV-oriented, and finally settled on Strata.

It worked for its purpose… but it was also very limited. It was just a static page, and every change required a lot of manual editing in HTML and CSS.

I considered building something from scratch with Angular (which I already knew), but I never found the right motivation to start that journey.

The first paradigm shift: file-based CMS

Another option was to use a CMS. I experimented with WordPress, and I liked the idea of having a “framework” to handle all the logic behind the scenes so I could focus on writing content. But I quickly ran into three problems:

- WordPress is primarily designed for blogs. Plugins make it very flexible, but using it for a CV website always felt a bit forced. (Not a real blocker, just a personal “smell” I’ve always had with WordPress.)

- The CV templates available were either ugly, paid, or really hard to customize.

- WordPress requires a MySQL database and a PHP runtime. Each of these adds cost to a hosting plan.

All of this made me look for alternatives.

The breakthrough came when I discovered the concept of file-based CMS. This idea, which started gaining momentum around 2020, offered an alternative: instead of using a database, the CMS would rely on the filesystem itself, saving content as regular files. This immediately caught my interest — especially because it meant I could avoid paying for a MySQL database.

That’s how I found Grav, a simple file-based CMS that worked perfectly. It even provided “skeletons” — pre-made templates you could unpack directly into your hosting space and start using right away.

I switched to Grav with a CV-themed skeleton called Hola, which I heavily customized for my needs. This version of the website lasted for years. It was flexible, easy to use, and very low-maintenance. Adding a new project, education, or work experience was as simple as editing a post and uploading a few photos — Grav handled the rest.

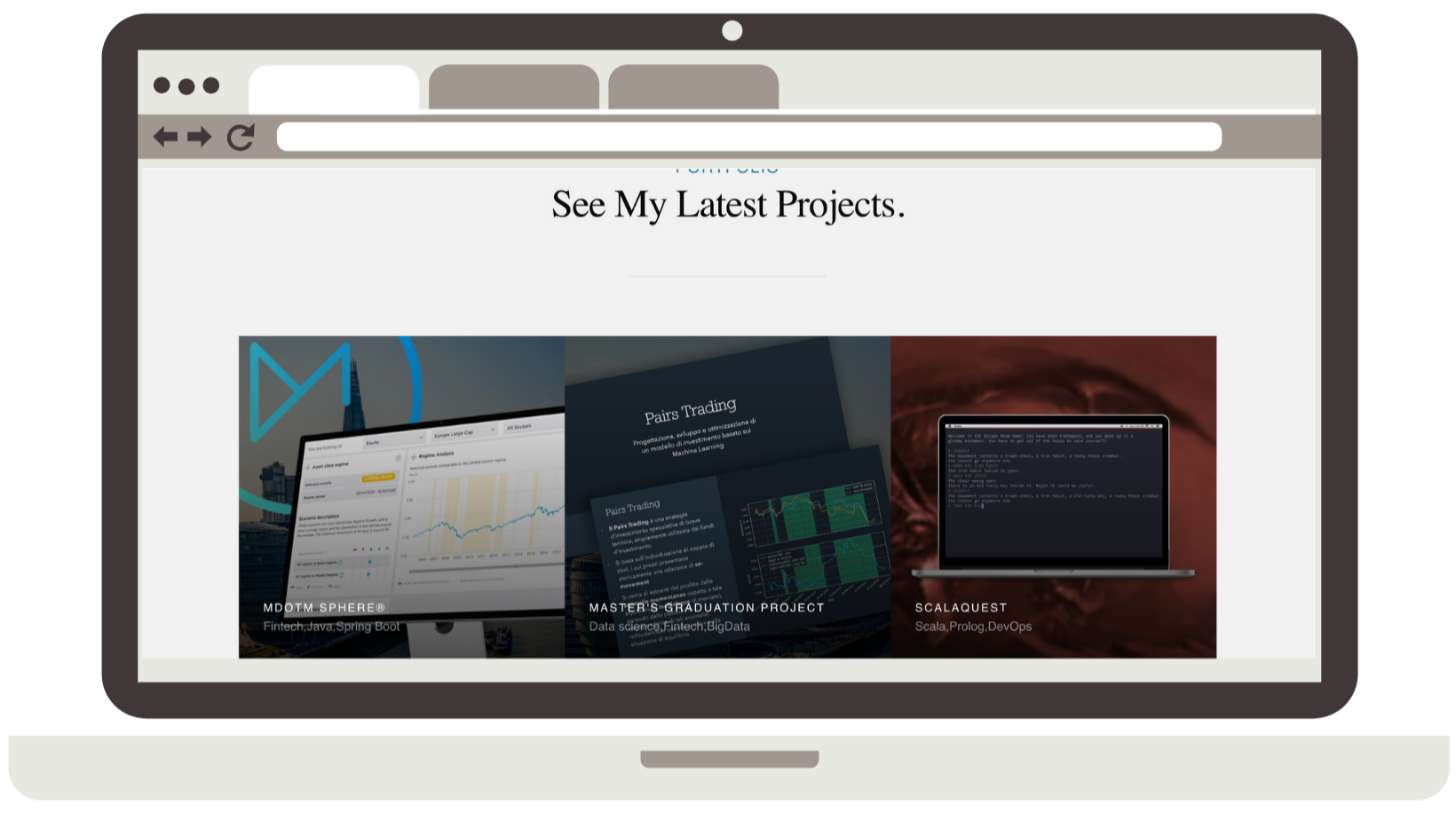

In the following years, I focused more on the content than the structure: updating graphics, adding descriptions of my work, and expanding the project list as I built new things.

The website is still available on the Internet Archive if you want to have a glimpse of how it appeared. The splash screen an typography were actually a bit different, to be honest, as it is not rendered correctly. My version also had a cool photo of myself on the background. The project section in particular, was quite fire with all those graphics 🔥

Shifting to the blog approach

At the beginning of 2025, I started rethinking the purpose of my website. My life had changed. Presenting myself only through a CV felt reductive. I’m not just a list of education and work experience.

Sure, you can download my CV if you want, but a CV doesn’t give me space to elaborate — to write full articles about projects or experiences, like the one you’re reading right now.

That’s when I decided to switch to a blog format. I created The Comepaolo Blog with a new purpose: to have a place where I could share and discuss my projects and experiences in depth.

The first version of the blog used, once again, a Grav theme: Mediator, a theme inspired by Medium’s design. It’s actually the same theme I still use today, even if a lot has changed under the hood (I’ll get to that in a minute).

I created the initial content, set up the skeleton of the site, and added a few customizations. I even contributed to the open source project of the theme with some optimizations.

I really enjoyed this approach, and I still do. But once again, something was missing. I decided to tackle that just a few weeks ago.

The second paradigm shift: Jekyll

More recently, I started experimenting with Jekyll. This came mainly from professional needs — I had to build a documentation website for an API set.

Jekyll is a static website generator. It lets you write your content as Markdown files (or other markup formats), completely separating content from presentation. It’s written in Ruby and uses a meta-language called Liquid to customize templates.

I fell in love with Jekyll almost instantly. It’s easy to use, the learning curve isn’t steep, and the concept behind it is clever and straightforward. GitHub even supports it out of the box for GitHub Pages, making it the de-facto standard for static websites.

While digging around, I discovered that the Mediator theme for Grav was actually a port of a Jekyll template — also called Mediator. At that point, the path was obvious: it was time to migrate my website to Jekyll and turn it into a real software project.

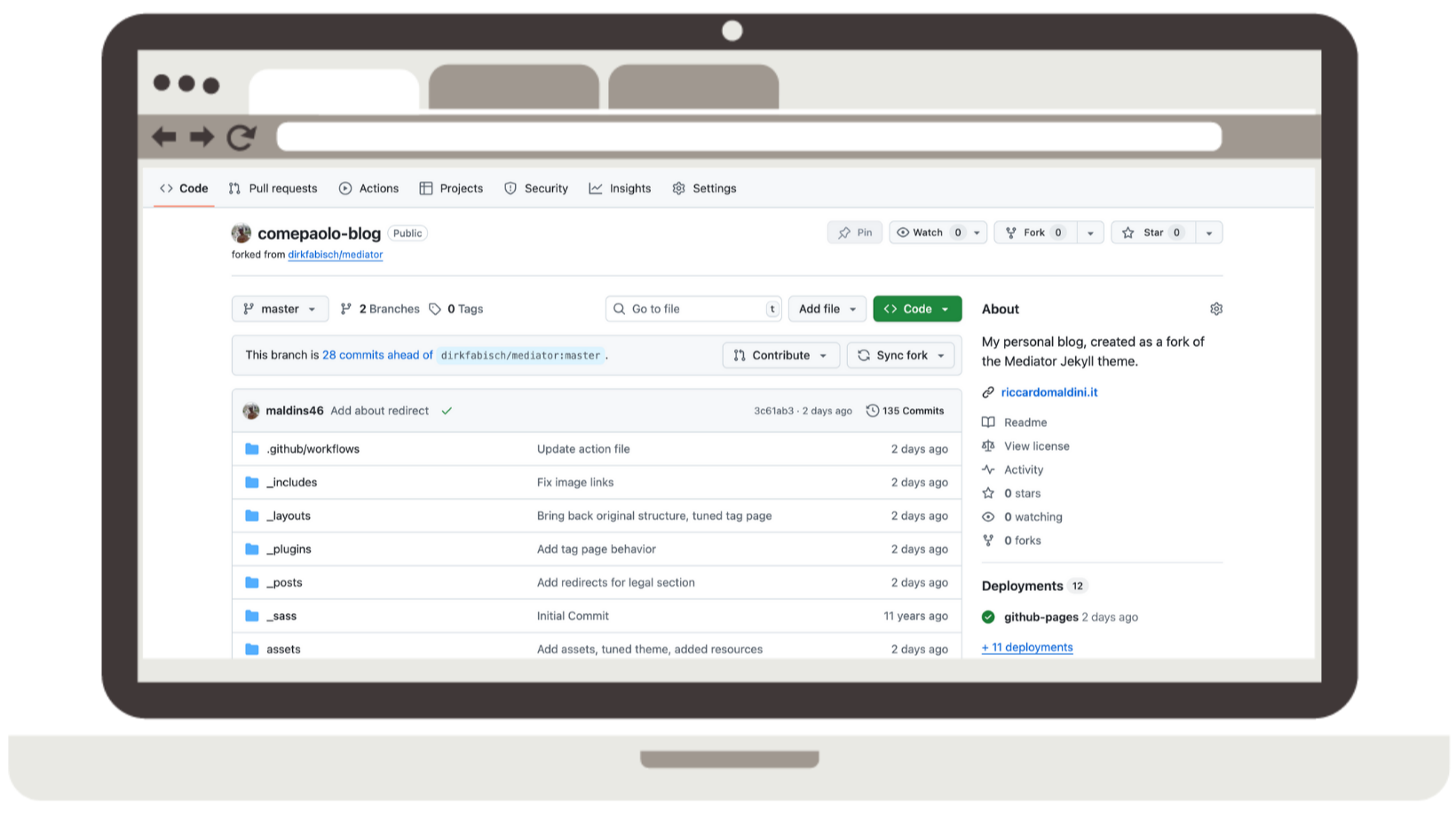

That’s when the idea for the comepaolo-blog GitHub project was born. And in less than a week, I completed the migration.

Let’s do a quick dive into it.

The comepaolo-blog Project

The current version of my website lives inside the comepaolo-blog project, which started as a fork of the Mediator Jekyll theme originally created by dirkfabisch. Mediator was designed as a clean, Medium-inspired theme, and it gave me a solid and elegant foundation to build upon.

I didn’t just fork it and leave it untouched, though. Over time, I shaped it to better reflect my needs and style. Some changes were simple customizations to the blog layout and sections, while others were more structural. For example, I extended the post tag system so that tags are now more prominent: each post shows its tags, and clicking on them brings you to a dedicated page listing all related articles. This feels much more natural when browsing older content.

Another important addition was the legal section. On my Grav site, I had hosted privacy policies and terms for my apps, and I wanted a smooth transition without breaking links. I rebuilt that section in Jekyll with a design consistent with the rest of the site, ensuring one-to-one retrocompatibility while improving the overall look.

Final essential additions, is the possibility to react and discuss about a given post. I introduced the possibility to do that using Giscus, an open source alternative to Disqus, based on the GitHub API and the Discussions feature of the repository itself, binding the discussions to the project.

I also worked on small but useful enhancements: extened favicon and metadata support, an updated FontAwesome version, and various layout tweaks that made the theme feel more polished for my purposes.

The biggest structural shift, however, was in how the site is deployed. Instead of manually uploading files or relying on a provider’s hosting tools, the whole process now runs through GitHub Actions. Each commit to the main branch triggers an automated build and deploy, and the output is directly published on GitHub Pages under my personal domain. This makes maintenance much lighter and aligns perfectly with a software engineering mindset: versioned, automated, and repeatable.

Looking back, this project has also been a sort of gym for me. It was the first time I extensively used Jekyll in a real setting, experimenting with Liquid templates and content organization, and figuring out how to bend the system to my needs. The migration itself—from Grav to Jekyll—was almost frictionless thanks to Markdown being the common ground, and it felt like a natural evolution rather than a rewrite.

Conclusion

From static HTML pages, to Grav, and now to Jekyll, the website has grown step by step along with my own path as a developer. What began as a simple CV placeholder has become a fully versioned, automated, and customizable blog.

The main advantage of this setup is that it behaves like a proper software project. Every article, design tweak, or configuration change is tracked in Git; deployment happens automatically through GitHub Actions; and the structure encourages experimentation without the fear of breaking things.

In the end, Comepaolo Blog is still just my personal space online—but one that reflects not only who I am, but also how I work.

And for me, that combination feels just right.