Every student coming from a science-related university has, at some point, experimented with writing documents in LaTeX. It’s a neat system designed for preparing documents, mostly used for academic purposes (nearly every scientific paper in the world is written in LaTeX), but not limited to that. Unlike tools such as Word, LaTeX is a document preparation system. It separates the content of the document from its presentation (the template), and makes it easy to represent complex elements like mathematical formulas in a textual way.

LaTeX templates are often professional and fine-tuned. The system itself feels almost like programming — technically, it’s a markup language — which is one of the reasons it became so popular in the scientific world.

I first discovered LaTeX at university, and I kept using it well beyond that context. One of the first “non-academic” uses I found was writing my Curriculum Vitae. At some point, I stumbled upon a template called LuxSleek-CV, originally created at the University of Luxembourg. It struck the perfect balance between elegance and readability, and it quickly became my official CV template.

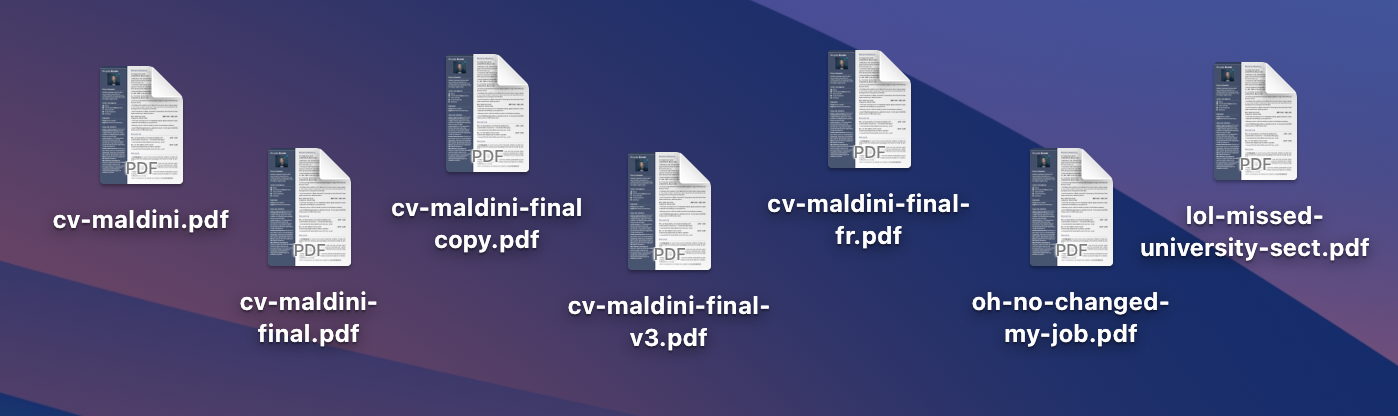

But writing it — whether in Overleaf or locally — soon revealed a bigger problem: versioning. Maintaining my CV wasn’t as simple as I’d hoped. Every update meant opening my editor, re-compiling the .tex file, exporting the PDF, and making sure I didn’t overwrite the wrong version. Over time, I ended up with a folder full of files named things like CV-final-v2.pdf, CV-updated.pdf, and of course, the infamous CV-really-final.pdf.

The struggle was real. At one point, I even gave up and switched to a simple Word document — probably the least “programmer” thing a programmer could do.

MaldiniCV

I spend my days working with version control, automation, and CI/CD pipelines. So I asked myself: why should my CV be exempt from those good practices?

That’s how MaldiniCV was born.

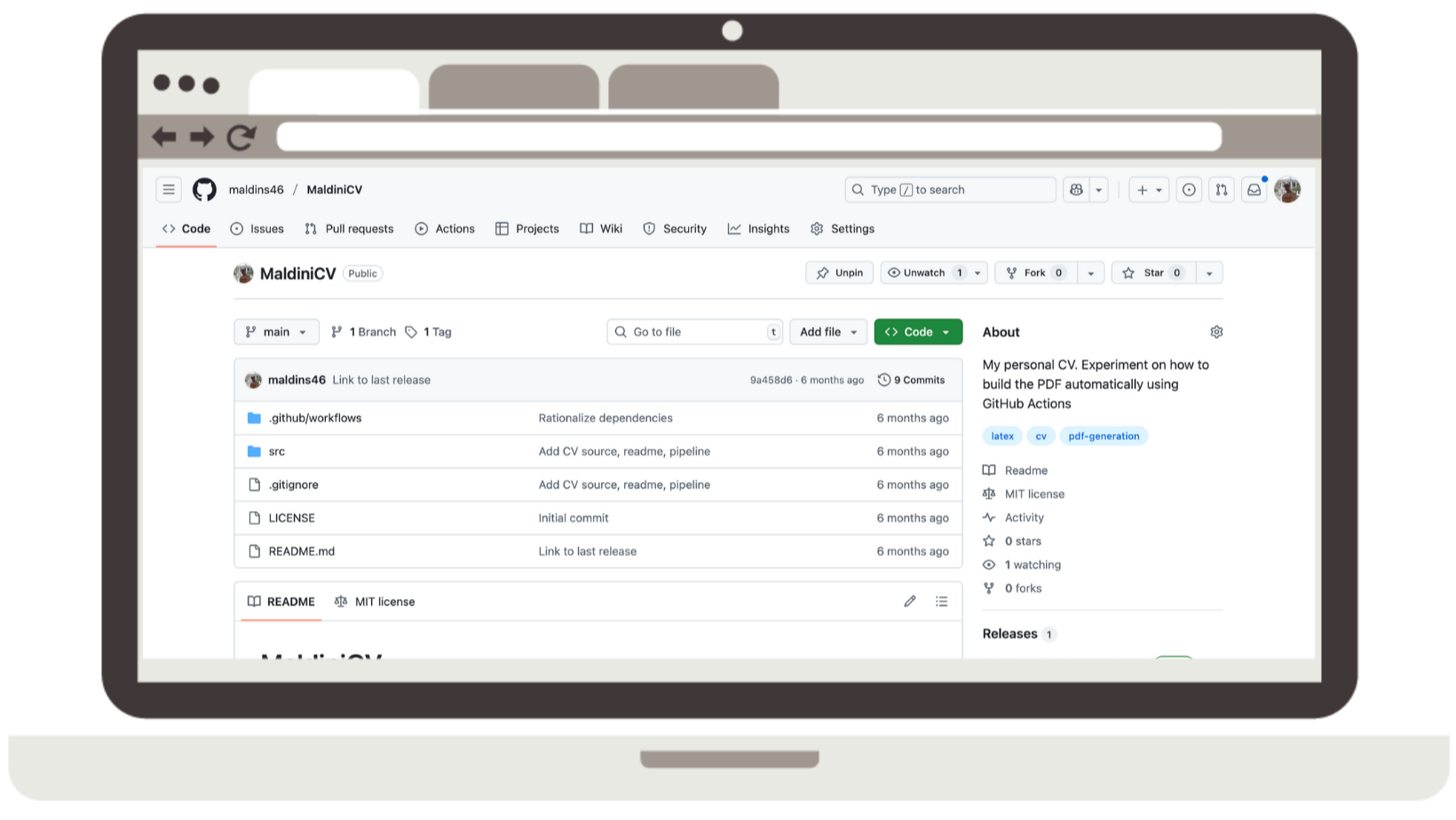

Instead of treating my resume like a static document, I decided to treat it like a piece of software. The content lives in a GitHub repository, written in LaTeX, and every time I want to “release” a new version of my CV, I simply push a Git tag. Behind the scenes, a GitHub Actions workflow compiles the source, generates a polished PDF, and publishes it as a release artifact. No manual steps, no confusion about which file is the latest — just clean automation.

From there, I structured the repository much like a small application. The src/ folder holds my main LaTeX file, while the .github/workflows/ directory contains the automation logic. The heart of it all is a workflow that installs the right TeX packages, builds the PDF, and attaches it to a GitHub release.

It might seem like overkill for a CV, but in practice it means I never have to think about formatting quirks or local environment issues again. If I can push code, I can update my resume.

The Workflow in Action

Here’s how it plays out in real life.

Let’s say I add a new job or a side project to my CV. I commit the change to the LaTeX source and push it up to GitHub. When I’m ready to “publish” the new edition, I tag it like I would a software release:

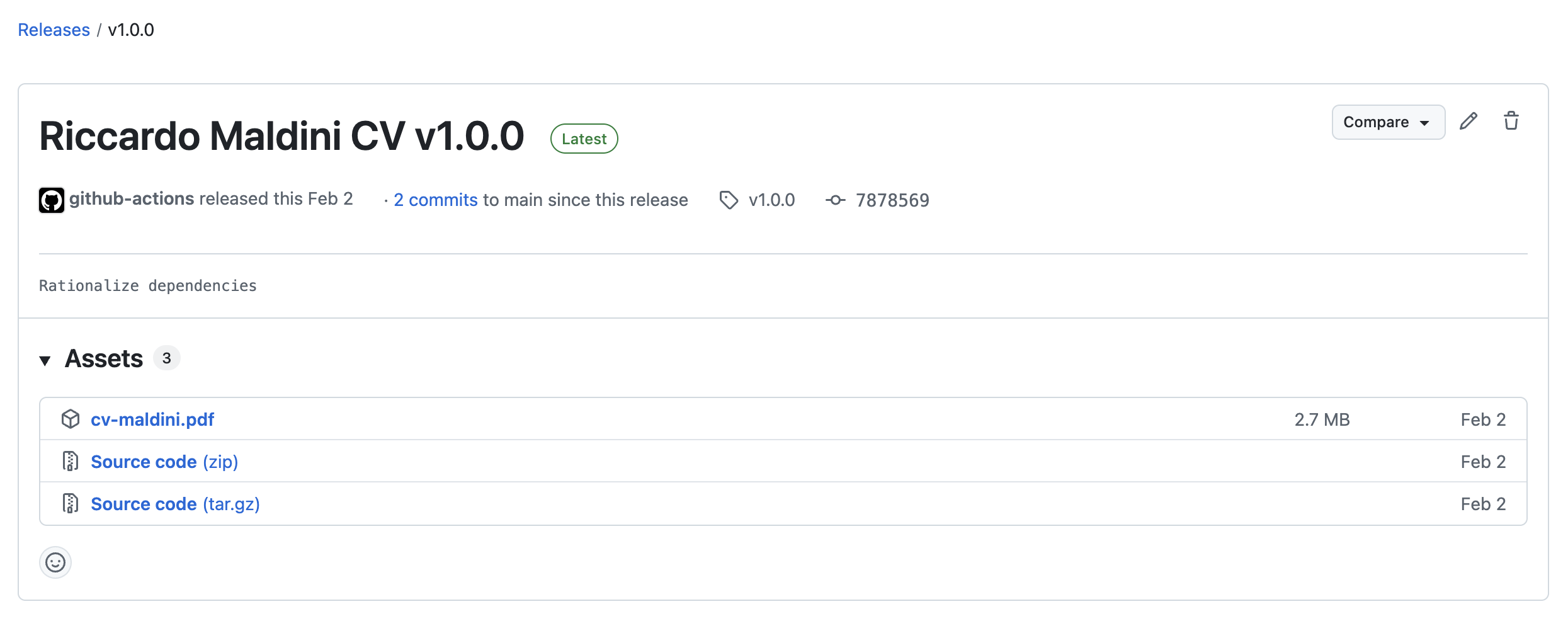

git tag v1.2.0

git push origin v1.2.0That tag is the trigger. GitHub Actions wakes up, installs a LaTeX environment, compiles my CV into a PDF, and creates a brand-new release in the repository. Within a minute or two, the final document is available to download straight from the Releases page.

What I love about this is how natural it feels. Versioning my CV is just like versioning code: the history is visible, the process is repeatable, and the output is always reliable.

Why Automate a CV?

On the surface, automating a CV might sound like a niche experiment. But I’ve found it surprisingly impactful.

For one thing, it eliminates all the little frictions of keeping documents current. I don’t worry about which PDF I last sent, or whether the formatting broke on my machine after a package update. The build process is consistent and runs in the cloud.

It also adds a layer of professionalism. Each release of my CV is versioned, timestamped, and archived. If someone asked me for the version I used in an application months ago, I could retrieve it instantly. It’s like having a changelog of my professional life.

And maybe the biggest win: peace of mind. I know that the link to my GitHub Releases page always points to an authoritative, up-to-date version of my resume. That alone makes it worth it. When needed, it is sufficient to provide to a recruiter a link to the latest release, as for any software library. Cool, isn’t it? :)

Right now, MaldiniCV does one thing well: it builds and releases my CV automatically. It is an open source project, you can even fork it and make it yours.

In the end, though, the beauty of this setup is its simplicity. My CV has become just another project — one that benefits from the same tools and practices I use every day as a software engineer. And that feels exactly right.