The Covid pandemic was one of the strangest periods of our lives.

For a few years, the world seemed to stop in its tracks. Streets went silent, cities emptied, and our daily routines were suddenly reshaped by lockdowns and strict restrictions on movement. It was a time that forced us to rethink society, freedom, and even ourselves.

And, of course, the reason behind it all was grim: illness and death. Millions were affected by the COVID-19 virus, while millions more went through an emergency vaccination campaign that promised a way out of the crisis.

In the middle of this, I was in my final year of university. The pandemic hit Italy in the early months of 2020, bringing with it the first nationwide lockdown. After a brief window of relief during spring and summer, new restrictions followed in the months ahead. Life felt like a cycle of reopening and shutting down, always with a lingering uncertainty about what would come next.

But after the first shock, something unique happened in Italy—something that, as far as I know, very few countries attempted. COVID-related data—numbers of infections, hospitalizations, deaths, and later vaccinations—were made publicly available as open data. Updated daily, they were shared on a dedicated GitHub repository. To me, this was remarkable: a real act of transparency and, in a way, efficiency from our Protezione Civile. It’s not common for governments to publish this kind of information in such a structured and accessible way. For once, Italy was not lagging behind but leading by example.

It was in the autumn of 2020 that I stumbled upon this repository. By then, the air was thick with news—some accurate, some misleading, some pure speculation. That’s when a thought struck me: what if I try to make sense of the data myself, instead of drowning in unverified headlines and rumors?

The CovidAnalysis Project

In November 2020, I started the CovidAnalysis Project, a not-so-original name for a small GitHub repository where I experimented with visualizing the data published by the Protezione Civile.

The repository looked very different in its early days compared to what you can see now. At first, I simply created basic plots using Matplotlib’s PyPlot library. Nothing fancy—just simple charts to get a clearer view of the numbers.

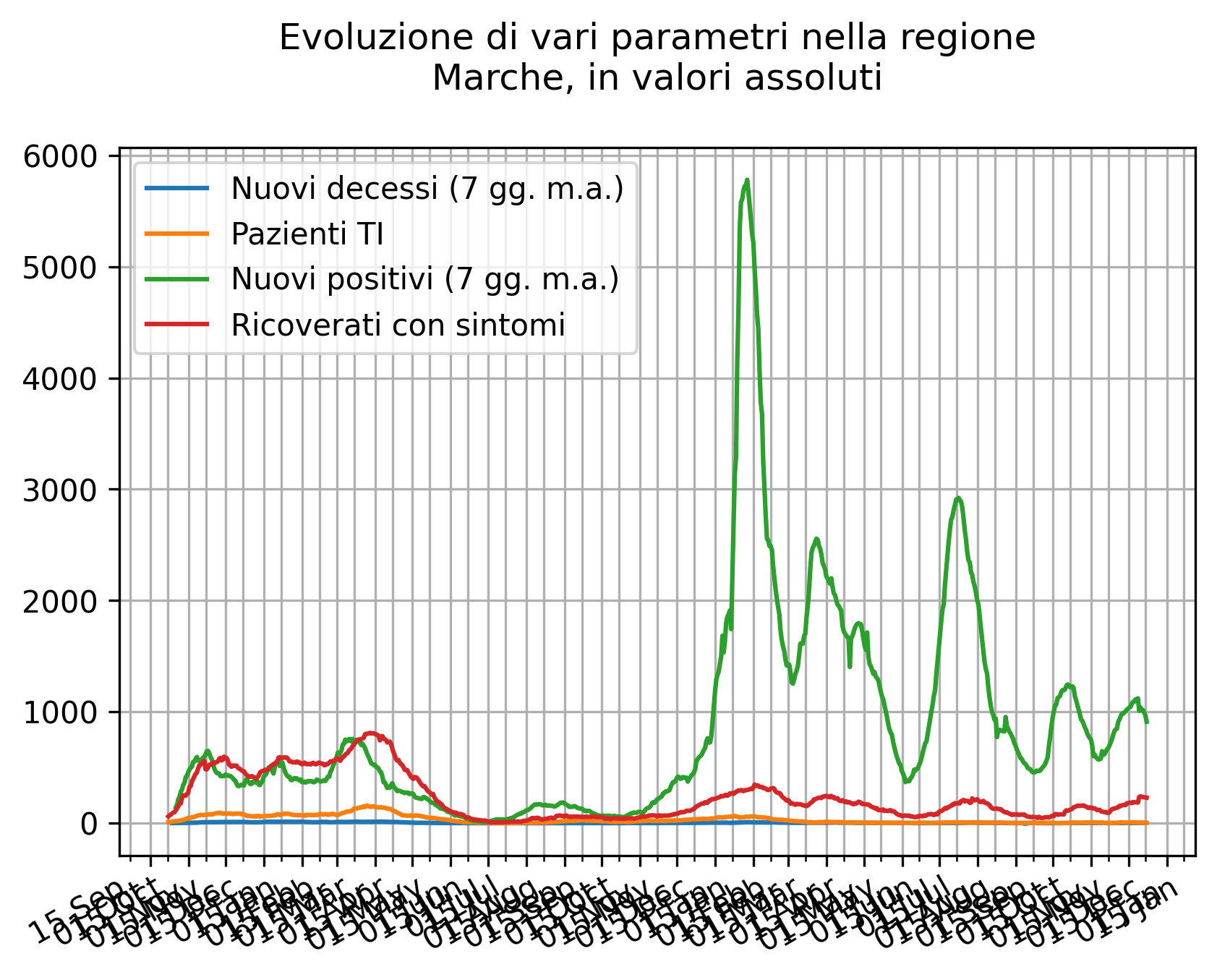

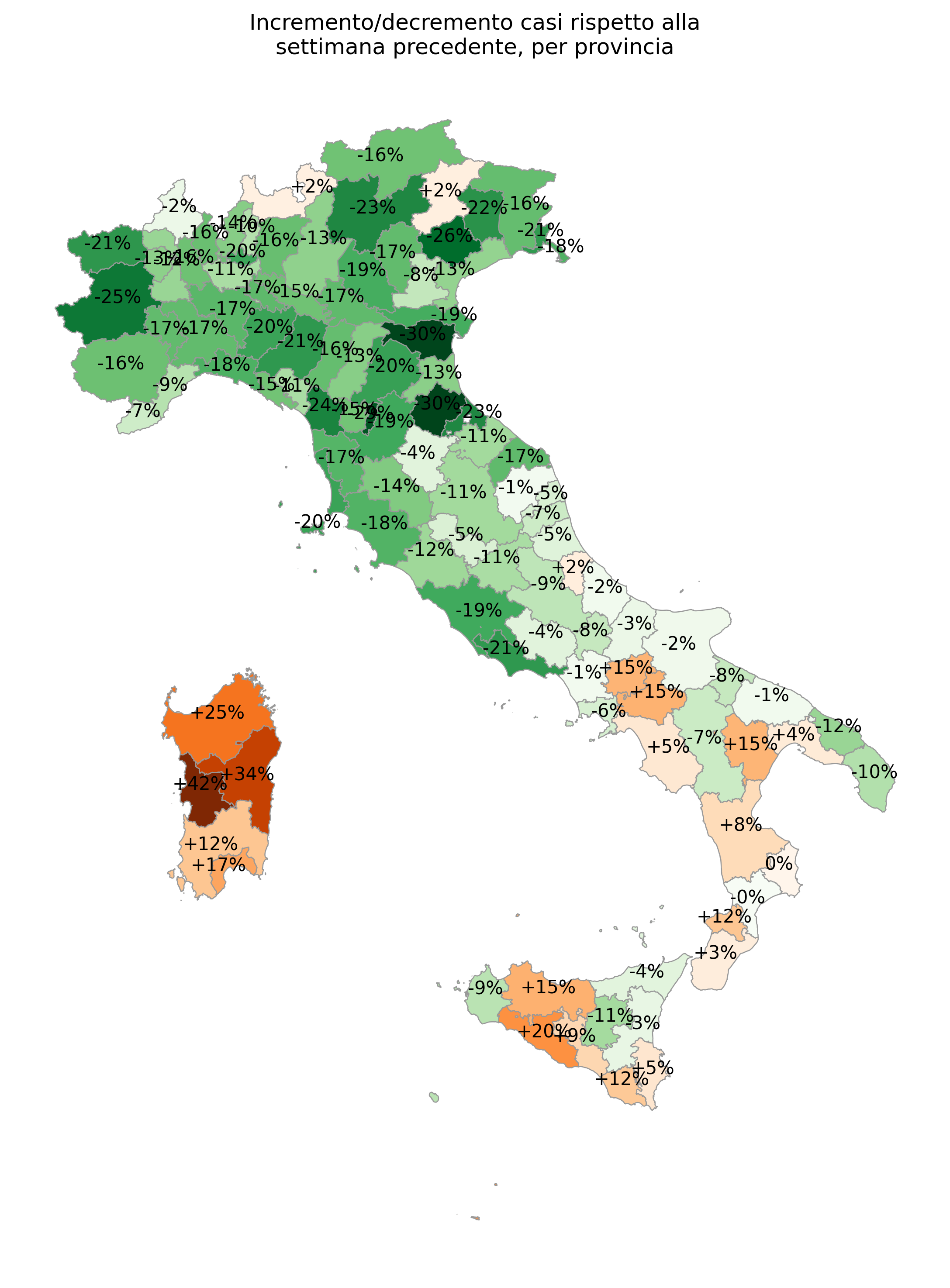

I began with the basics: the number of deaths and infections, both as weekly incidence and absolute values. I was particularly interested in the data from my own region, Le Marche, since local information wasn’t always easy to find in national news.

As I got more comfortable, I started experimenting with more advanced analysis. I built geographical maps showing data per region and province, calculated derivatives to track daily increases or decreases, and even tried to estimate the infamous RT and R0 indexes per region—later adding vaccination data as well. To do this, I followed the methodology published by the Protezione Civile—at least as closely as the available data would allow.

What made this project truly fascinating was its immediacy. The data wasn’t historical or archived: it was unfolding in real time. Every day I could update my charts and see the impact of new cases, comparing how infections rose or fell against the thresholds the government used to determine lockdown measures.

For example, the well-known color-coded system, zona rossa, arancione, gialla, was tied to metrics like hospital occupancy, ICU admissions, deaths, and of course the RT index. With CovidAnalysis, I could visualize those very same parameters and even make short-term predictions about which restrictions might come next (with a fair margin of uncertainty, of course), basically fact-checking what I was seeing on national news.

CovidAnalysis quickly became more than just a coding exercise. For me, it was a powerful way to make sense of the chaotic reality around me, and to replace anxiety with understanding. Looking back, I realize this was my unofficial crash course in both data analysis and software engineering.

Let’s Go Public!

By December 2020, I started realizing that all the information I was generating was pure gold. It felt like a waste to keep it only for myself. Wouldn’t it be great to share these insights with others? Maybe I could publish the charts on a website, or even automate the whole process so people could see daily updates without me manually running scripts.

With that spirit, I kicked off the second phase of the project.

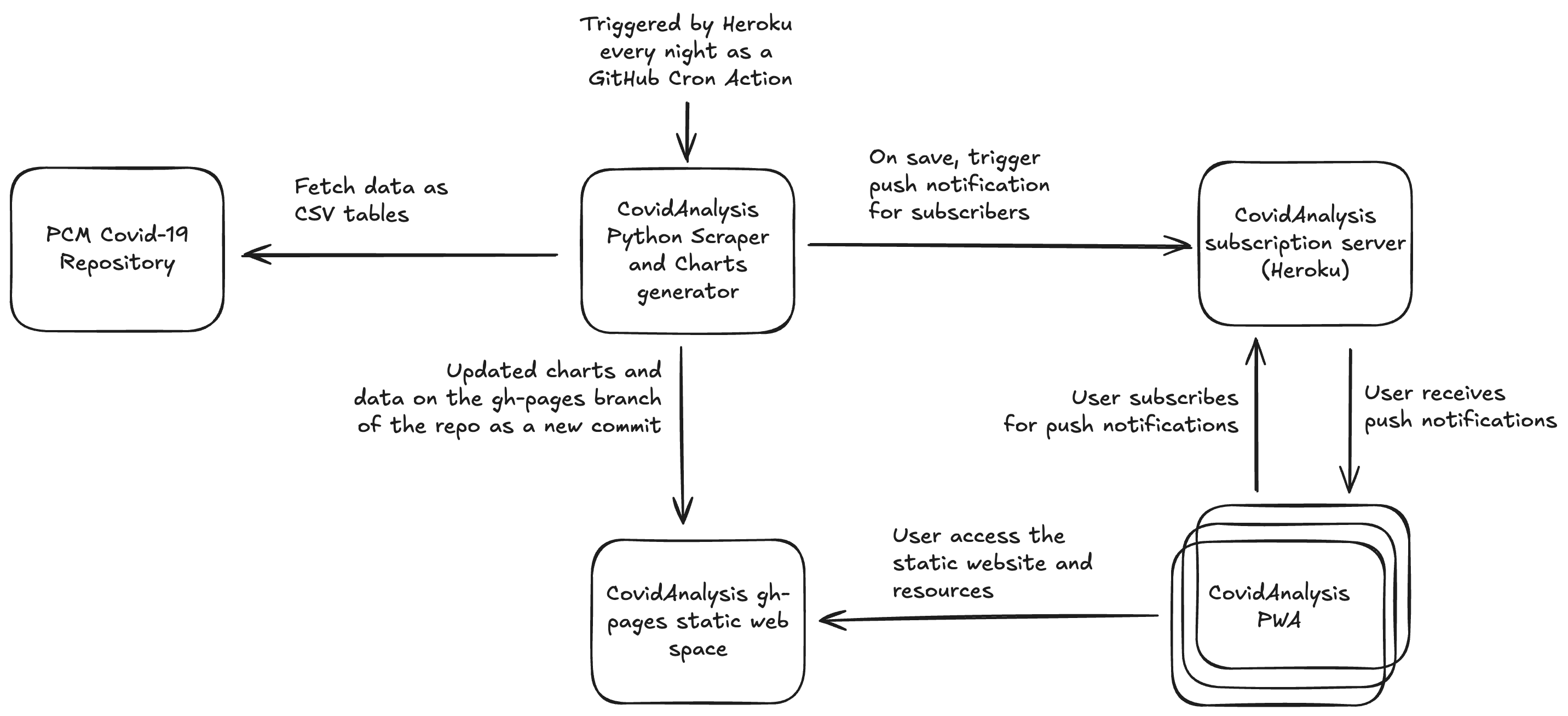

The first step was automation. Initially, the repository only contained Python code to fetch data from the Protezione Civile’s GitHub repo, load it into a DataFrame, and generate plots. But I wanted this to happen automatically, every single day, without me lifting a finger.

So I set up a GitHub Action with a cron job. Every morning at 4 a.m., the Action would spin up a container, run the Python scripts, generate fresh plots, and export them as JPEGs. The images were then committed back into the repository in an autogenerated commit, on the deploy branch. Not the most elegant solution, I admit—but it worked perfectly for what I needed.

The second step was exposing the data. This, for me, was the most exciting part.

At the time, I was also wrapping up my Web Development exam at university, where we had studied frameworks like Angular, Vue, and React. I had always enjoyed frontend development—whether for mobile apps (shoutout to my BetAssist project!) or for the web. What fascinated me most was the immediacy: you write some code, refresh, and boom—you see the result instantly.

Among the frameworks, Angular quickly became my favorite. I loved how it offered a complete, opinionated structure backed by Google, with official plugins and endless npm libraries to expand its capabilities. Personally, I found it more cohesive than React or Vue, which often felt fragmented or lacking a common standard. Of course, that’s just my opinion; the rest of the world probably disagrees with me!

So I decided to build a small Angular Progressive Web App (PWA) to display all the charts my scripts generated daily.

In less than a week, I had the first version up and running. To keep things simple (and free), I hosted it directly on GitHub Pages. Zero cost, minimal friction, and suddenly my data wasn’t just mine anymore—it was available to anyone.

Tweaks and Optimizations

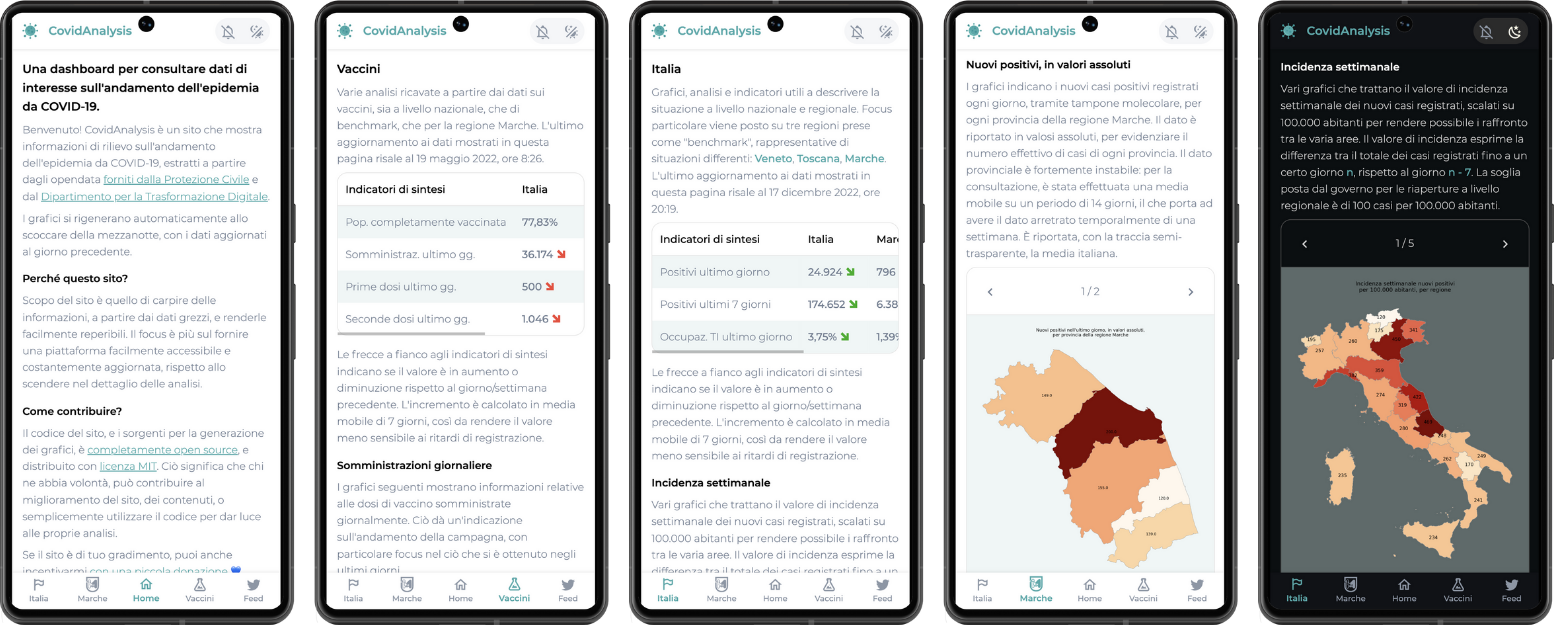

Over time, the website became more than just a data portal—it turned into a playground for experimenting with style and features. I started treating it as a design exercise, trying out Angular’s Material UI and fine-tuning the details of the interface.

I also restructured the site into multiple sections: one dedicated to national Italian data, another focused on my home region of Le Marche, and a third where I pulled in pandemic-related news directly from Twitter (back then it was still Twitter, not X).

On the design side, I couldn’t resist adding a dark mode, along with an automatic theme switch based on the user’s system preferences. Small touches, but they made the app feel much more polished and modern.

But the feature I’m most proud of was the notification system. At some point, I decided to push the limits of Progressive Web App capabilities by experimenting with push notifications. The idea was simple: whenever new daily data was processed, users would receive a notification.

To achieve this, I combined service workers with a minimal backend to handle topic subscriptions. I deployed the server on Heroku (at the time, the easiest and most developer-friendly choice). Although the service is no longer running today, the source code is still available under the CovidAnalysis Server repository.

Conclusion

What started as a small experiment in my final year of university quickly grew into something much bigger. CovidAnalysis was never meant to be a polished product. It was a playground where I combined curiosity, coding, and a very real need to make sense of the world around me.

Along the way, I learned how to fetch and process open data, automate workflows with GitHub Actions, build and deploy a frontend with Angular, and even push the boundaries of PWAs with notifications. But more than the technical lessons, this project gave me something deeper: a way to cut through the noise of misinformation and uncertainty during one of the most confusing times of our lives.

Looking back, I see CovidAnalysis as more than just a coding project. It was my way of understanding reality through data, of feeling a little more in control when everything around us felt unpredictable. CovidAnalysis wasn’t just about charts and scripts; it was about finding clarity in chaos, and about taking the very first real steps in my journey as a software engineer.