2019 was a year of big changes in my life.

I had just graduated with my bachelor’s degree that February. My course was Informatica Applicata: that’s roughly equivalent to Computer Science outside Italy. I already liked programming, even though, looking back from where I am now, I was just at the beginning of my journey.

I still remember my thesis well: Utilizzo del pattern Publish-Subscribe e dei Message Broker nell’implementatione di giochi online Multiplayer e Applicazioni Distribuite 🗣🗣️📢📢🔥🔥

A very roboant name for a thesis, isn’t it? It was based on experiments I did with message brokers (mainly RabbitMQ) and the publish-subscribe pattern, during an internship at a software company in my town.

It was an interesting topic, one that hadn’t been covered during my studies. But as I discovered during my internship, message brokers are essential in microservice, or even simpler multi-service architectures, especially when handling asynchronous communication.

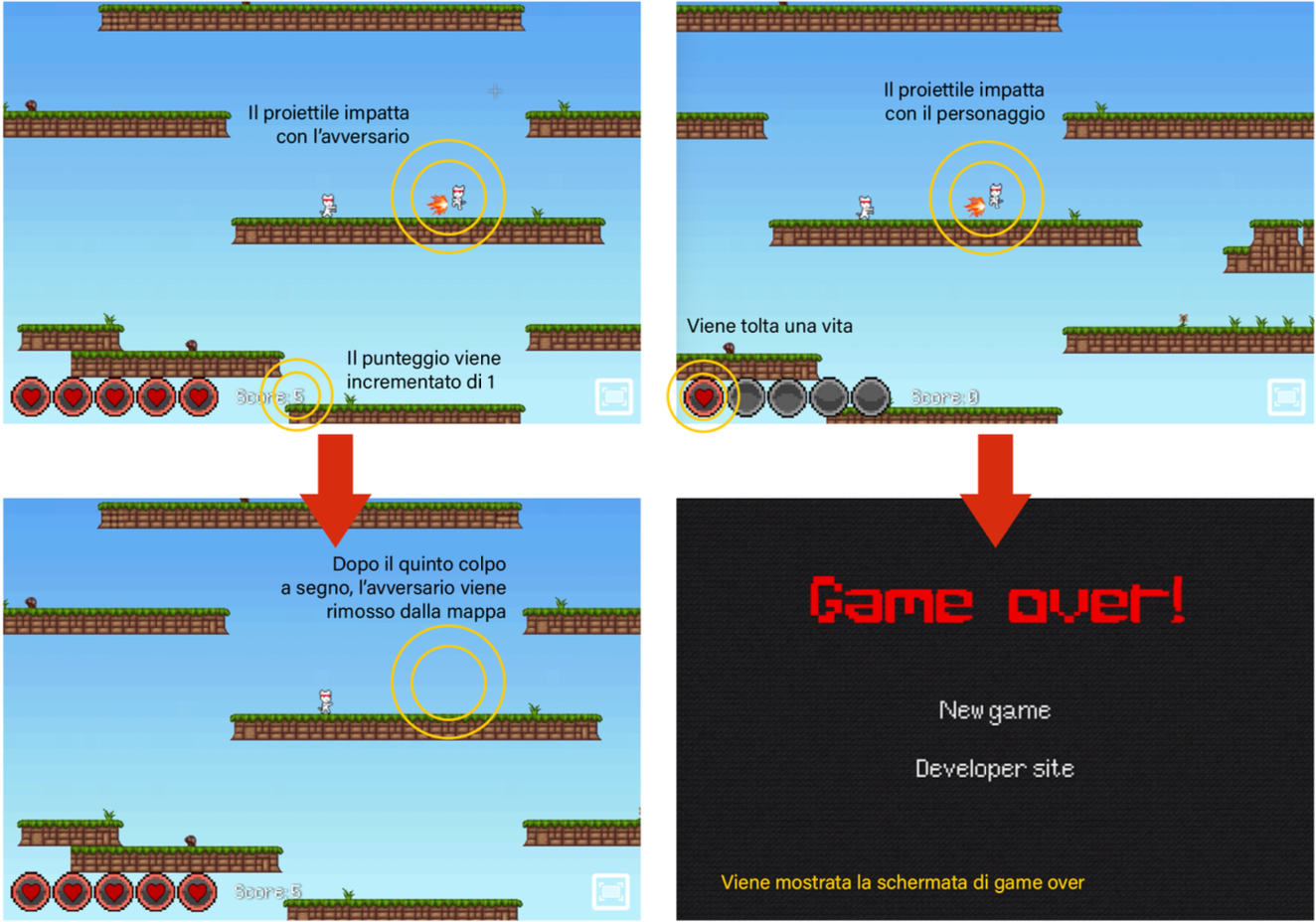

As part of my thesis, I also built a small browser-based multiplayer game. It was simple but fun: every player controlled a ninja cat who could throw fireballs at others on a Super Mario–like map. I created everything with an HTML canvas, following an online guide (simpler times!).

The real highlight, though, was the backend. Building on my RabbitMQ experiments, I developed a small Node.js application that used RabbitMQ to manage multiplayer rooms—for example, creating topics for broadcasting messages between players. Communication between client and server ran over WebSocket.

On the day of my thesis defense, I even prepared a live demo! Without the skills to host it on a real server, I hacked together a setup on my home PC, exposing both the client and backend to the internet. It worked, and the professors could interact with the game live. Their surprised faces made it worth it.

So, why am I telling you all this? Because one of those professors was particularly impressed. At that time, he was launching a university spin-off company aimed at developing small games and tools for teaching children in elementary and middle school the basics of programming—without requiring advanced technical knowledge. After seeing my demo, he invited me to join his company.

It was an unexpected but exciting proposal. Since my thesis ended in February, I had a few free months before starting my master’s degree in September (though, honestly, I wasn’t even sure yet if I wanted to pursue a master’s). With nothing to lose, I decided to seize the opportunity and see where life would take me.

CodyColor Multiplayer

About a month later, I joined the company: Digit Srl.

This meant extending my apartment rental in Urbino for a few more months. It turned out to be fun, as some of my friends were still at university — so in many ways, it felt like an extension of student life.

Digit was a small start-up, backed by the University of Urbino. And the academic roots were clear: out of four employees, two were researchers continuing their projects, while the other two were recent graduates — me and another guy.

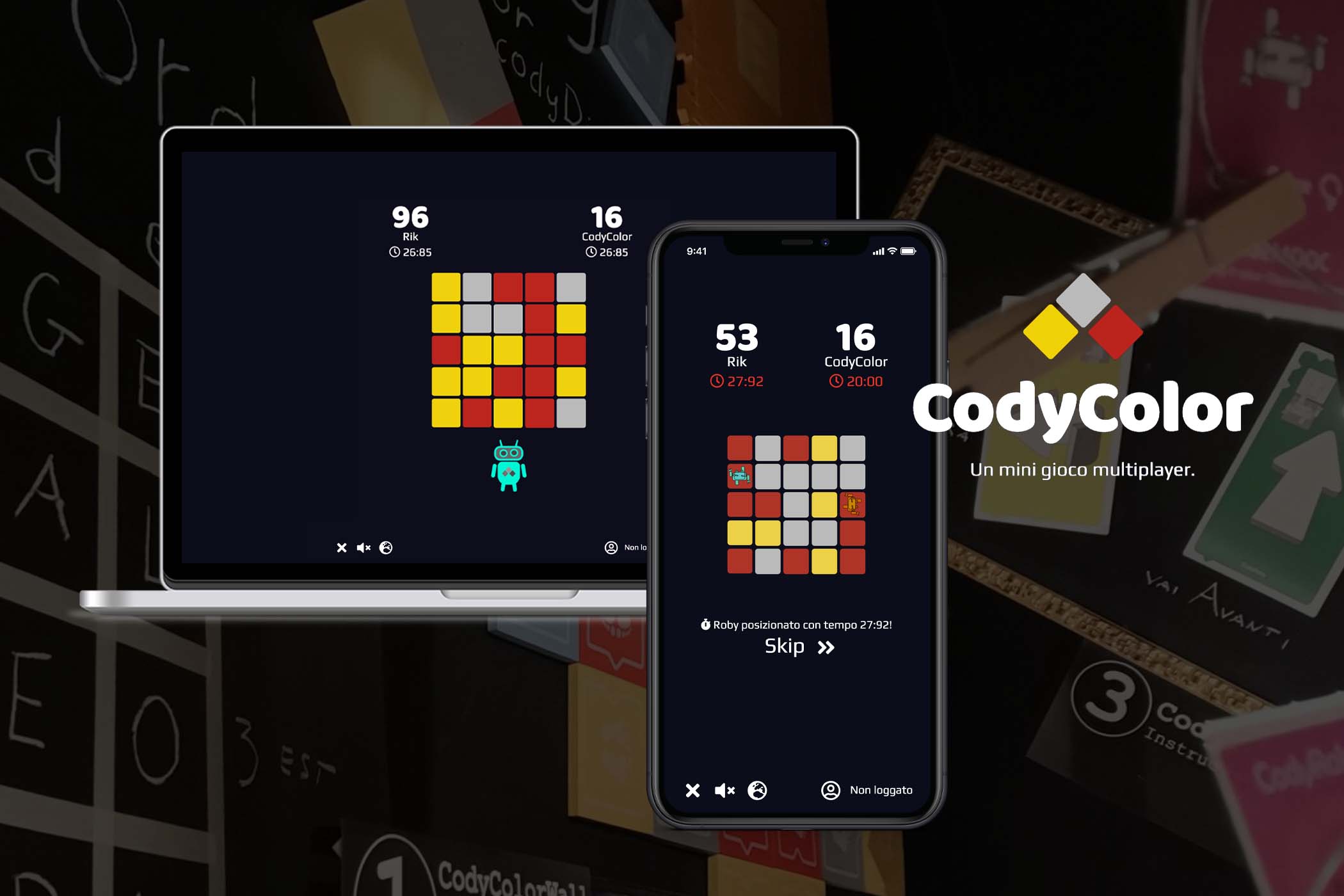

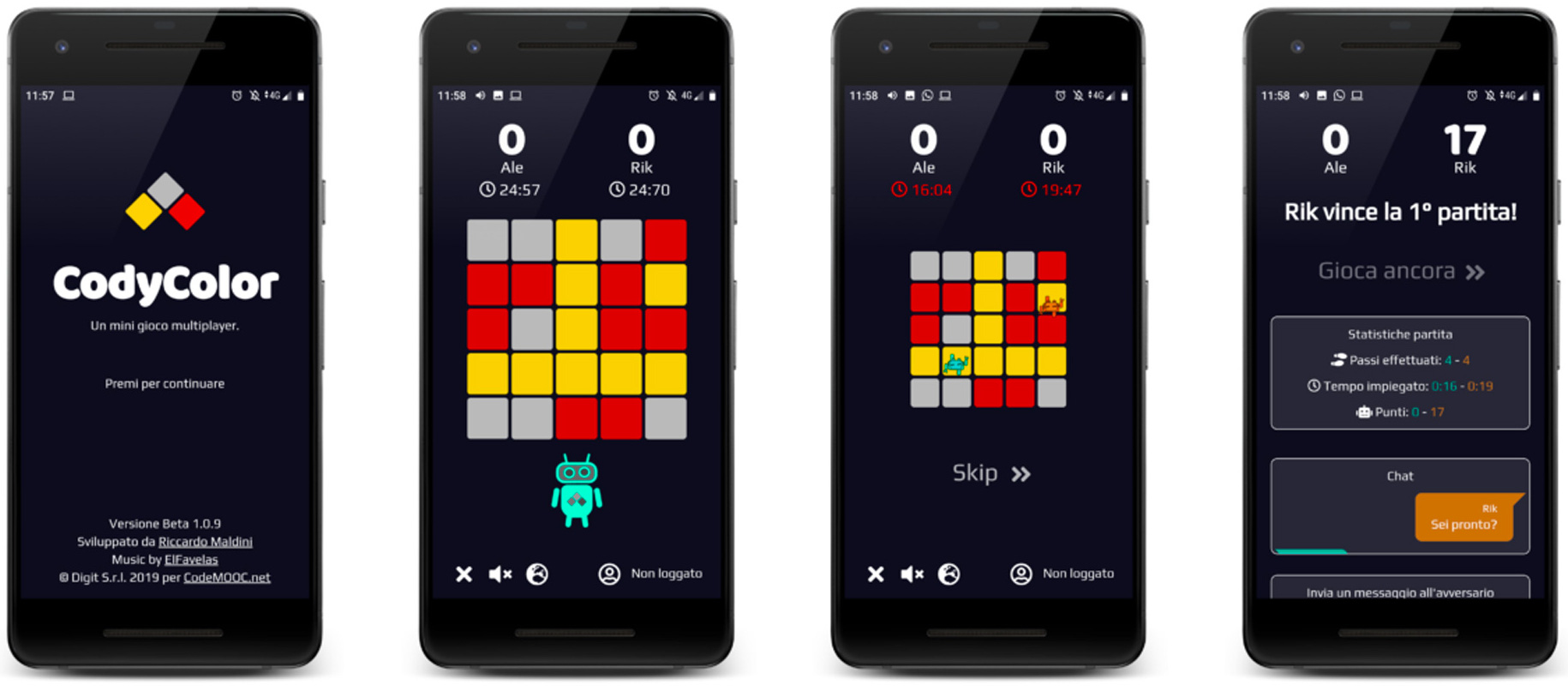

My focus was on building a multiplayer game called CodyColor.

To clarify: CodyColor is actually a coding method: a set of simple rules that can be turned into different types of games. The company already had an offline version, played with physical tiles and pawns, and the plan was to bring it online.

Here are the basic rules:

- The playing field is a 5x5 grid (though it can be any size).

- Each square can be colored yellow, red, or grey.

-

Each player controls a robot, Roby, who moves based on the color of the square:

- Yellow → rotate 90° left

- Red → rotate 90° right

- Grey → move forward

After a turn, Roby continues to the next square in its new direction.

Bringing It to Life

Digitalizing CodyColor was not easy, especially since I had zero experience with game development. But I did what I always do: learn by example.

AI assistants weren’t available yet, so I spent hours searching the web for similar projects, tutorials, and resources. Bit by bit, experiment after experiment, I gained confidence.

For the frontend, I used AngularJS (yes, the grandparent of Angular). For the backend, I built a NodeJS app, communicating with the client via a single WebSocket channel. All of the heavy work (esatablishing the connection, maintain the tunnel up, establish the actual communication) was made possible (both on client and server) via StompJs, a library implementing the publish-subscribe pattern over WebSocket, which was in turn a intermediary to publish and consume messages from a RabbitMQ message broker, to handle communication between game rooms. Architecturally, it was similar to my previous project, so I wasn’t starting from scratch.

With some help from the colleagues, the project began to take shape. I first built a single-player version with a simple AI opponent (not “AI” as we know it today—just a basic algorithm generating paths with varying difficulty). I worked with the HTML canvas, added drag-and-drop robots, and integrated resources from the offline version.

To my surprise, the game started to come alive. Within a month, I had a working single-player prototype. The code was messy, but it worked—and that was enough to keep going.

Switching to Multiplayer

The next step, of course, was multiplayer.

Here I drew heavily on what I had learned with my Ninja Cat project—except this time, real players would be interacting.

Over the following months, we managed to make the magic happen again. We didn’t just create a multiplayer version—we also built a battle royale mode, where dozens (even hundreds) of players could compete in the same room.

We added a shared leaderboard and even allowed players to log in with federated identities (Facebook, Twitter, and Google+ were still around back then). Using Firebase Authentication and Firestore, we could manage this almost for free, given the small user base. Simpler, cheaper times indeed.

As a fun spin-off, I developed a wall version of the game. It ran on a TV in our company’s display window. A QR code invited passersby to scan it, instantly joining a match against the AI visible on the screen. It was immersive, playful, and surprisingly fun to watch people try it out.

Conclusion

In the end, I had built a real product with my own hands—despite starting with almost no knowledge of JavaScript.

CodyColor Multiplayer remains one of the projects I’m most proud of. Not because of its complexity, nor its code quality (honestly, the code was terrible). But because it showed me what I was capable of: learning on the go, solving problems step by step, and pushing through challenges instead of giving up.

It’s one of the projects where I grew the most as a developer—and it all started with a simple opportunity I decided to take.